“Alaska is home to over 21,000 known species, including mammals, birds, fish, invertebrates, plants, fungi, and microbes. Polar bears are at the top of the Arctic food chain. Regarding hunting, they are stealthy ninjas of the Arctic. They’ve mastered some clever techniques to catch their favorite prey—seals”

Polar bears in ecosystem (Ursus maritimus) are more than just iconic Arctic predators — they are keystone species that reflect the health of Alaska’s rapidly changing environment. As apex predators, they help maintain the delicate balance of marine ecosystems. But their future in the ecosystem is increasingly uncertain due to climate change, industrialization, and habitat loss.

In this article, we explore their ecological significance, their cultural role among Alaska Native communities, the challenges they face in the ecosystem, and the global efforts underway to protect them.

Significance of Polar Bears’ Ecosystem in Alaska

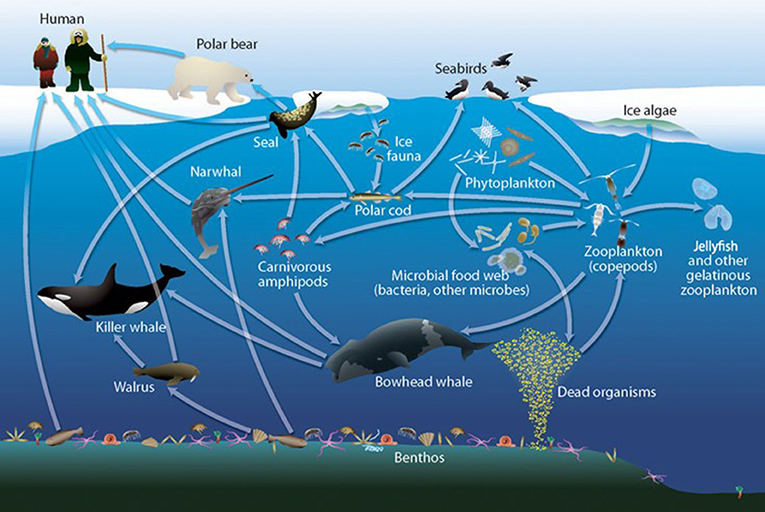

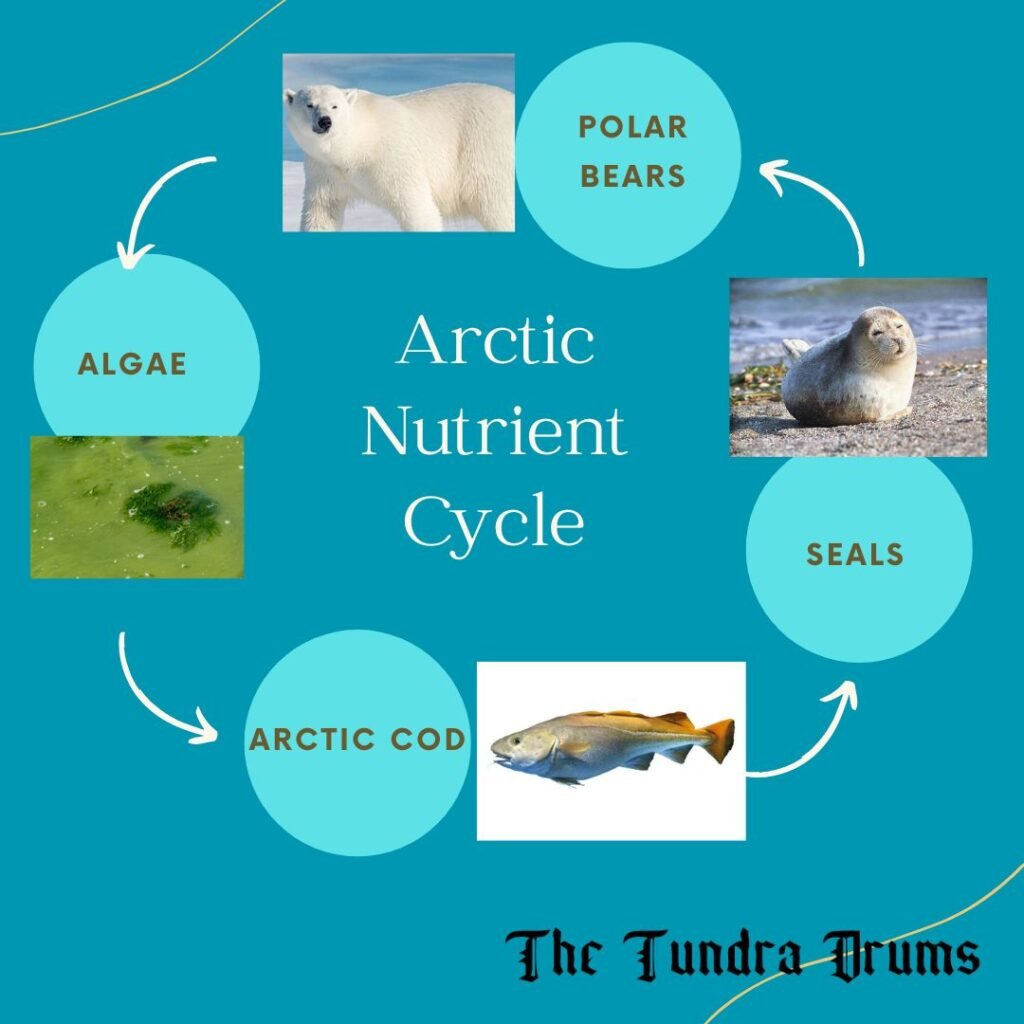

Polar bears sit at the top of the Arctic food web. Their primary prey is ice-dependent seals, such as ringed and bearded seals. By regulating seal populations, they contribute to the stability of the marine ecosystem, which in turn affects fish populations and overall ocean health.

Beyond their predatory role, they contribute to nutrient cycling in the Arctic ecosystem. The remains of their hunted prey provide sustenance to scavengers like Arctic foxes and birds, as well as decomposers that enrich the tundra soil. This process helps redistribute energy across trophic levels, supporting the broader Arctic food web.

Perhaps most critically, they are considered an indicator species. Their health reflects the condition of the Arctic ecosystem. A decline in polar bear populations often signals larger environmental issues, such as declining sea ice, disrupted food chains, and ecosystem stress caused by warming temperatures.

“The presence and health of polar bears tell us about the broader state of Arctic marine biodiversity.” – Alaska Wildlife Alliance

Cultural Importance to Indigenous Communities

They hold deep cultural and spiritual significance for Indigenous communities in Alaska ecosystem. For centuries, Native Alaskans have coexisted with them, integrating them into traditional stories, ceremonial practices, and subsistence lifestyles.

Sustainable hunting practices, governed by community ethics and knowledge passed down through generations, highlight the importance of balance with nature. For these communities, protecting polar bears isn’t just a conservation effort — it’s a matter of preserving cultural identity.

“Polar bears are not just animals to us. They are part of our way of life.” – Alaska Native Elder (as quoted in Natural Habitat Adventures)

The Threats Facing Alaska’s Polar Bears

1. Climate Change and Sea Ice Loss

The single greatest threat to them in today’s ecosystem is climate change. Rising global temperatures are melting Arctic sea ice — the primary hunting ground for them.

As the ice disappears earlier in spring and forms later in autumn, they have fewer months to hunt seals and build critical fat reserves. This leads to malnutrition, lower reproductive rates, and increased mortality — especially for cubs.

2. Industrial Activities and Habitat Disturbance

Oil and gas exploration, shipping traffic, and Arctic tourism are expanding across Alaska’s northern coast. These activities fragment polar bear habitats, disrupt migration paths, and increase the risk of oil spills that can poison both the bears and their prey in the ecosystem.

Noise pollution and human-wildlife conflict also increase as they are forced onto land in search of food, leading to dangerous encounters with people and reduced survival rates.

Conservation Efforts: A Race Against Time

National Protections

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has listed them as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act since 2008. This status offers some legal protections for their habitat and mandates continued research and policy development to support recovery.

Conservation groups like the Alaska Wildlife Alliance are also working with Indigenous communities to track populations, advocate for stronger climate policies, and minimize human-wildlife conflict.

International Agreements

Polar bear conservation is a global responsibility. The Agreement on the Conservation — signed by the five nations (Canada, the U.S., Russia, Norway, and Greenland/Denmark) — promotes international cooperation in research, management, and habitat protection.

Nutrient Cycling

Polar bears contribute to nutrient cycling by transporting nutrients from the ocean to the land.

Primary Producers

The primary producers in the Arctic food web are the organisms that produce their food through photosynthesis and form the base of the food web. These include

- Phytoplankton

- Algae

- Terrestrial Plants

Primary Consumers

The primary consumers in the Arctic food web are herbivores that feed on the primary producers. These animals include:

- Zooplankton

- Krill

- Insects

- Small Mammals

Secondary Consumers

The secondary consumers in the Arctic food web are carnivores that feed on the primary consumers. These animals include:

- Fish

- Seabirds

- Marine Mammals

- Land Animals

Tertiary Consumers

The tertiary consumers in the Arctic food web are apex predators that feed on the secondary consumers. These animals include:

- Polar Bears

- Orcas

- Arctic Foxes.

What Can Be Done?

- Support climate action: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is vital to preserving polar bear habitats.

- Protect critical sea ice zones: Limit industrial development in key polar bear hunting areas.

- Elevate Indigenous voices: Support co-management efforts that include traditional ecological knowledge.

- Educate and raise awareness: Use platforms to share science-backed stories about their conservation.

Conclusion

Polar bears are not just symbols of the Arctic wilderness in ecosystem — they are sentinels of environmental change, vital predators, and keepers of cultural heritage in Alaska.

Their survival depends on global climate action, robust policy enforcement, and continued collaboration between scientists, Indigenous communities, and conservation organizations. If we protect them, we are also protecting an entire ecosystem — and the future of the planet itself.