Alaska’s native spruce bark beetle, Dendroctonus rufipennis, has killed millions of spruce across Southcentral Alaska, driven by warm winters and plenty of stressed, large-diameter host trees. Since 2016 alone, more than 2.2 million acres have been affected, reshaping forests and elevating wildfire and safety risks near communities. Homeowners can reduce losses by managing slash and firewood outside the beetle flight season and by removing hazard trees in time.

Meet the culprit: a rice-sized beetle with outsized impact

The spruce bark beetle is Alaska’s most damaging forest insect. It bores through bark to lay eggs in the phloem, where larvae feed and cut off a tree’s nutrient transport. In “quiet” years, it prefers storm-thrown or already stressed spruce; during outbreaks, it overwhelms even healthy trees. In Alaska, its main hosts are white, Lutz (white × Sitka hybrid), Sitka, and sometimes black spruce

How the outbreak grew—and where it is now ?

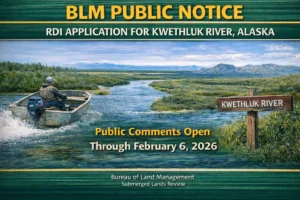

Alaska has seen big beetle pulses before, notably on the Kenai Peninsula in the 1990s, when ~2.3 million acres were hit at the peak and many large spruce died. A new wave starting in 2016 spread across the Matanuska-Susitna, Kenai Peninsula, Denali, and Anchorage areas, cumulatively topping 2.2 million acres as of 2025. Recent mapping shows 2024–25 activity concentrated in Denali (≈14,640 acres) and Mat-Su (≈14,915 acres), with Kenai activity dropping >90% from 2023 and Anchorage nearly quiet (~30 acres).

Why climate and tree size matter ?

Warm springs help adult beetles take flight earlier and survive winter. In Alaska, adults typically fly from mid-May to mid-July, kicking off new attacks when temperatures reach ~60°F (16°C). Outbreak risk also climbs where there’s an abundance of large-diameter spruce, fresh blowdown, or freshly cut slash, which are beetle magnets.

What beetle- killed forests mean for people and wildlife

- Safety & Fire: Dead standing spruce become “hazard trees” along roads, trails, and yards. More dry fuel can intensify wildfires at the wildland-urban edge—one reason Anchorage is removing beetle-killed material in parks and greenbelts.

- Ecology: After the die-off, the sun reaches the forest floor. Fast-growing hardwoods (birch, aspen/willow) and shrubs fill in, often boosting browse for moose and habitat diversity, while surviving young spruce stock the next generation. In Denali, managers expect local spruce losses but regional forest composition to remain mixed over time.

Recognizing an infested tree

Early signs include fine reddish boring dust at the bark base, small pitch tubes (less common when trees are drought-stressed), and woodpecker activity. Needles fade from green to reddish brown over months after an attack, but by then the tree is already lost. (For a thorough homeowner guide, UAF’s Extension has an excellent field PDF.)

What you can do (homeowners & landowners)

Timing is everything.

- Avoid creating spruce slash (cutting live spruce, felling, or milling) during the flight period (mid-May to mid-July). If you must, process immediately, debark, chip, mill to dimensional lumber, split and stack off the ground, or bury slash so beetles can’t use it.

Reduce attraction & hazards.

- Remove or treat wind-throw and fresh logs before flight season; these are prime brood sites.

- Identify and remove hazard trees (dead or dying spruce that threaten structures, trails, or power lines). Municipal and agency crews in Southcentral are actively doing this for public safety; mirror that approach on private property.

Consider repellents—carefully.

- The semiochemical MCH (3-methyl-2-cyclohexen-1-one) can repel spruce beetles, and research—including Alaska trials—shows it can reduce attacks on high-value trees or small stands. However, results in Alaska are mixed, and MCH alone is not a silver bullet during heavy outbreaks; think of it as one tool in an integrated strategy. Consult local experts before purchasing.

Get local advice.

- The Alaska Division of Forestry & Fire Protection maintains an up-to-date spruce beetle hub with maps, FAQs, and homeowner guidance. UAF Cooperative Extension also offers practical management courses and handouts tailored to Alaska.

The bottom line

Spruce bark beetles are a natural part of Alaska’s forests, but warmer conditions and lots of big, susceptible spruce have supercharged recent outbreaks. The good news: outbreaks are patchy and cyclical, and proactive yard and woodlot practices go a long way. Manage slash outside flight season, deal with hazard trees, and use expert-vetted tools where they make sense. That keeps homes safer, trails open, and leaves room for the next forest to grow.