| Spoken Languages in Alaska represent a diverse and culturally rich tapestry, reflecting the state’s unique heritage and community identities. |

Language is not just a tool for communication but a vital part of cultural identity, heritage, and community cohesion. It shapes thoughts, influences interactions, and connects people to history. This is especially true in Alaska, where the rich tapestry of spoken languages reflects the state’s diverse cultural heritage. The spoken languages in Alaska form a unique and vibrant linguistic landscape, with 23 distinct languages, most belonging to two main language groups. However, understanding these languages is crucial for appreciating Alaska’s history and recognizing the importance of preserving these linguistic treasures.

Spoken Languages in Alaska

The following are the languages spoken in Alaska:

- Alutiiq

- Iñupiaq

- Ahtna

- Deg Xinag

- Koyukon

- Han

- Eyak

- Holikachuk

- Lower Tanana

- Tanacross

- Tlingit

- Upper Kuskokwim

- Aleut

- Central Alaskan Yup’ik

- Eskaleut languages

- Athabaskan languages

- Central Siberian Yupik language

- X̱aad kíl

- Upper Tanana

- Coast Tsimshian

1. Alutiiq

The language spoken in Alaska has two dialects, Koniag and Chugach. It covers regions from the Alaska Peninsula to Prince William Sound, including Kodiak Island. Sadly, out of a total population of about 3,000 Alutiiq people, only around 400 still speak the language, indicating a decline in fluent speakers.

| Alutiiq | Translation |

| Cama’i | Hello |

| Quyanaa | Thank you |

| Spraanikam | Happy Holidays |

2. Iñupiaq

Iñupiaq, spoken throughout much of northern Alaska, is closely related to the Canadian Inuit and Greenlandic dialects. This linguistic connection creates a rich cultural bond among the Inuit communities across regions. The dialects have unique vocabularies and suffixes, contributing to the richness and depth of the language. For example, ‘tent’ is “tupiq” in North Slope and ‘house’ in Malimiut, while ‘house’ is “iglu” in North Slope.

However, the sound differences between dialects can make communication challenging. For example, ‘they are cooking’ is “iarut” in the Seward Peninsula but “igarut” in North Alaskan.

| Iñupiaq | English Translation |

| Tautugniaqmigikpiñ | Good-bye |

| Quyanaq | Thank you |

| Qaimarutin | Welcome |

| Nayaaŋamik Piqaġiñ | Merry Christmas |

| Qanuq itpich? | Hello, how are you? |

3. Ahtna

Extensive linguistic research on Ahtna began in 1973 under James Kari and culminated in the publication of a comprehensive language dictionary in 1990. However, despite these efforts, the number of fluent speakers still needs to be higher, posing challenges to the language’s long-term vitality and preservation.

| Ahtna | Translation |

| Tsin’aen | Thank you |

| C’ehwggelnen Dzaen | Merry Christmas |

| Slatsiin | My friend |

4. Deg Xinag

Deg Xinag, also known formerly as Deg Hit’an and previously referred to pejoratively as Ingalik, is the Athabascan language spoken by the communities of Shageluk and Anvik and by Athabascans near Holy Cross below Grayling on the lower Yukon River. Out of approximately 275 Deg Hit’an people, only 40 individuals speak the language. However, limited intergenerational transmission and educational resources threaten the revitalization efforts of the language.

| Deg Xinag | Translation |

| Dogedinh | Thank you |

| Sits’ida’on | My friend |

5. Koyukon

The spoken language of Alaska, Koyukon, is also known as Denaakk’e. It is the Alaska Athabascan language with the most significant territorial spread. The name Denaakk’e [də-nae-kuh] comes from the word “denaa,” meaning ‘people,’ and the suffix “-kk’e,” meaning ‘like’ or ‘similar,’ literally translating to ‘like us.’ It is spoken in three dialects—Upper, Central, and Lower—across 11 villages along the Koyukuk and middle Yukon rivers, reflecting a rich linguistic diversity.

Meanwhile, significant work has been done to document the language, notably by Jesuit Catholic missionary Jules Jette from 1899 to 1927 and native Koyukon speaker Eliza Jones since the early 1970s.

However, despite a total population of about 2,300, only 300 people actively speak Koyukon, indicating a decline in fluent speakers. The language is difficult to pass down to younger generations, threatening its long-term survival.

| Koyukon | Translation |

| Dzaanh Nezoonh | Hello |

| Baasee’ | Thank you |

| Gganaa’ | Good luck, friend |

6. Han

Hän is an Athabascan language spoken in the Alaskan villages of Eagle and Dawson, Yukon Territory. Of approximately 50 Hän speakers in Alaska, around 12 are fluent. The writing system was developed in the 1970s, and the Alaska Native Language Center has conducted significant documentation.

The Hän language plays a crucial role in preserving the cultural identity and heritage of the Hän people. However, the decline in fluent speakers makes passing the language on to younger generations challenging.

| Han | Translation |

| Mahsi’ | Thank You |

| Nijaa | Our friends |

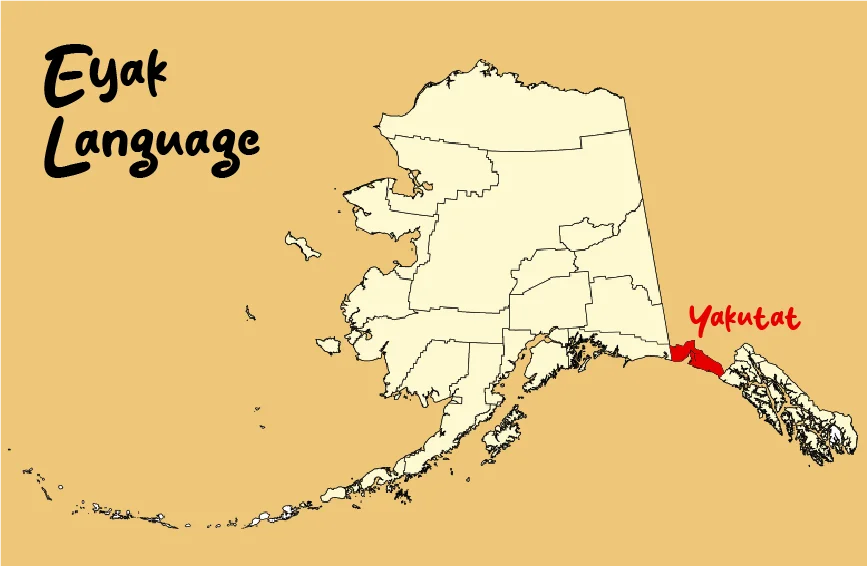

7. Eyak

In the 19th century, the Eyak language was widely spoken along the southcentral Alaska coast, stretching from Yakutat to the Copper River delta. The language represents a rich cultural heritage, with traditional stories, historical accounts, and poetic compositions preserved. By the 20th century, however, it was only spoken in Eyak, significantly reducing its geographic range. Currently, Eyak is represented by about 50 people, none of whom are fluent speakers, highlighting the critical risk of the language.

| Eyak | Translation |

| Awa’ahdah | Thank you |

8. Holikachuk

Holikachuk is an Athabascan language spoken by the Innoko River community, originally from the village of Holikachuk. It’s vital to the Innoko River community’s cultural heritage and identity. The language enriches the Athabascan language family’s diversity and contributes to Alaska’s linguistic landscape. Sadly, the language is not widely passed down to younger generations, ultimately causing a decline in native speakers. Also, there are limited educational resources and opportunities for learning Holikachuk.

| Holikachuk | Translation |

| Etla, s’coy | Hello, my grandchild |

| Da’ent’a | How are you? |

| Dogadinh | Thank you |

9. Lower Tanana

Tanana Athabascan is spoken primarily in Nenana and Minto, two villages on the Tanana River below Fairbanks. The Athabascan population in these villages is about 380, with approximately 30 speakers of the language. Meanwhile, significant linguistic work has been conducted on Tanana Athabascan. The advanced age of the remaining speakers poses substantial challenges for intergenerational transmission and language revitalization efforts.

| Lower Tanana | Translation |

| Basi’ | Thank you |

| Segena’ | My friend |

| Do’int’a? | Hello (how are you?) |

10. Tanacross

Tanacross is an ancestral language of the Mansfield-Ketchumstock and Healy Lake-Joseph Village bands, preserving a rich cultural heritage. However, with only about 65 speakers, the language risks becoming endangered. Despite the practical alphabet and published resources, more efforts are needed to ensure the language’s survival and transmission to future generations.

| Tanacross | Translation |

| Tsin’ęę | Thank You |

11. Tlingit

Tlingit (Łingít) is spoken in coastal Southeastern Alaska, from Yakutat south to Ketchikan. The Tlingit population in Alaska is approximately 10,000 across 16 communities, with about 500 fluent speakers. Meanwhile, it preserves the rich cultural heritage and traditions of the Tlingit people, including their ancient legends and stories. However, the transmission of the language to younger generations is declining, posing a challenge to its preservation. Furthermore, despite available resources, there are limited opportunities and support for learning Tlingit in formal educational settings.

| Tlingit | Translation |

| Tsu yéi ikḵwasateen | See you later |

| Gunalchéesh | Thank You |

12. Upper Kuskokwim

Upper Kuskokwim Athabascan is spoken in Nikolai, Telida, and McGrath villages in the Upper Kuskokwim River drainage. The language faces the risk of becoming extinct among about 160 people, with only 40 speakers left. Despite the efforts, limited resources and support may hinder more extensive preservation and revitalization initiatives.

| Upper Kuskokwim | Translation |

| Chwh | Big |

| Goya | Small |

13. Aleut

Unangam Tunuu, or Aleut, is a branch of the Eskimo-Aleut language family. Its territory in Alaska includes the Pribilof Islands, the Aleutian Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula west of Stepovak Bay. Learning and speaking Unangam Tunuu helps preserve the unique cultural heritage of the Unangax̂ people. The language holds significant historical value, reflecting the interactions between the Unangax̂ people and Russian explorers, primarily through the Russian Orthodox Church’s efforts to promote literacy. With fewer than 100 fluent speakers remaining, the language is at risk of becoming extinct. Despite efforts to develop educational materials, people have limited resources and opportunities to learn Unangam Tunuu, especially in a modern context.

| Aleut | Translation |

| Aang | Hellow |

| Iĝamanakuq? | I’m fine |

| Qaĝaasakung | Thank You |

14. Central Alaskan Yup’ik

Central Yup’ik is the largest of the state’s Native languages in population and number of speakers. Meanwhile, of approximately 21,000 people in the Yup’ik community, about 10,000 are speakers of the language.

It lies geographically and linguistically between Alutiiq and Siberian Yupik. In Central Yup’ik, the apostrophe indicates a long “p,” unlike in Siberian Yupik. Yup’ik represents the language and the name of the people, yuk ‘person’ plus pik ‘ natural.’

Despite a significant number of speakers, the language faces challenges due to the declining number of fluent speakers in some areas. The existence of multiple dialects, such as General Central Yup’ik, Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, Nunivak, and Egegik, presents challenges in creating standardized educational materials and resources.

| Central Alaskan Yup’ik | Translation |

| Cama-i | Hello (good to see you) |

| Waqaa | Hi! What’s up? |

| Piura | Good-bye |

| Quyana | Thank You |

15. Eskaleut

The Eskimo-Aleut languages, spoken by the Inuit and Unangan (Aleut) peoples in Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and eastern Siberia, are rich in cultural heritage. Unangan is the self-name of the Aleut people, highlighting their identity and history.

The Eskimo-Aleut language family includes a variety of dialects, such as Unangam Tunuu (Aleut), with its two surviving dialects and the Yupik and Inuit divisions. This diversity reflects the adaptability and resilience of these languages across different regions.

The term “Eskimo” has been historically used to refer to the Inuit, but it is now recognized as offensive. The persistence of this term in linguistic contexts can be seen as a negative legacy of colonialism.

| Eskaleut | Translation |

| Aang | Hellow |

| Qilachxizax̂ | Good Morning |

16. Athabaskan

The Athabaskan language is one of the largest North American Indian language families, consisting of about 38 languages. Meanwhile, speakers of Athabaskan languages often use the same term for their language and ethnic group, similar to how ‘English’ refers to both the language and the people. These terms usually incorporate words for ‘person’ or ‘human,’ such as Navajo diné. However, many Athabaskan languages face a decline in fluent speakers, threatening their survival. Balancing the preservation of traditional languages with the demands of modern society can be challenging. Also, it makes it difficult to maintain the relevance and usage of these languages.

| Athabaskan | Translation |

| Yá’át’ééh | Welcome |

17. Central Siberian Yupik

St. Lawrence Island Yupik, also familiar as Siberian Yupik, is spoken in the villages of Gambell and Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island. This language is nearly identical to those spoken across the Bering Strait in Siberia’s Chukchi Peninsula. In 1971, researchers at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks updated this orthography, creating several educational resources, such as an initial dictionary and a practical grammar guide.

Despite these positive developments, Siberian Yupik faces several challenges. On the Siberian side, the total population of Siberian Yupik people is about 900, with only 300 speakers remaining. Unfortunately, no children in Siberia learn it as their first language, posing a significant threat to the language’s survival in that region.

This historical lack of written materials delayed the development of effective educational resources. Though modern orthography and curriculum materials now exist, revitalizing and maintaining the language remains ongoing.

| Central Siberian Yupik | Translation |

| Natesiin? | How are you? |

| Esghaghlleqamken | Good-bye (I’ll see you) |

| Igamsiqanaghhalek | Welcome (thank you for coming) |

18. X̱aad kíl

Xaad Kíl is spoken in Hydaburg, Craig, Kasaan, and Ketchikan communities in Southeast Alaska. Despite its uniqueness, there are only four speakers in Alaska and about 20 in Haida Gwaii in British Columbia. Xaad Kíl consists of two dialects: Northern and Southern. Alaskan Haida speak a sub-dialect of the Northern dialect called Kaigani Haida. Learning Xaad Kíl allows individuals to connect deeply with the culture and history of the Haida people.

Despite educational support, maintaining and revitalizing the language is challenging due to the low number of fluent speakers. The absence of a genetic relationship to other languages can make learning and teaching Haida more complex.

| X̱aad kíl | Translation |

| Sán uu dáng g̲íidang? | How are you? |

| Díi ‘láagang. | I’m fine. |

| Sán uu dángs G̱íidang? | And how are you? |

19. Upper Tanana

Upper Tanana Athabascan is spoken mainly in the Alaska villages of Northway, Tetlin, and Tok, with a small population across the border in Canada. Although there are 105 speakers, the language is at risk due to the few people who speak it fluently.

Furthermore, Paul Milanowski established the writing system in the 1960s. Despite ongoing efforts, linguistic documentation has progressed slowly, potentially hindering comprehensive language preservation.

| Upper Tanana | Translation |

| Nts’ąą’ dįįt’eh? | How are you? |

| Suu’ | Good, fine |

| Tsen-‘įį | Thank you |

20. Coast Tsimshian

The Tsimshian language has been spoken in Metlakatla on Annette Island since 1887. The community relocated from Canada to the southeastern tip of the Alaska Panhandle, guided by missionary William Duncan. Sadly, out of the 1,300 Tsimshian people residing in Alaska, only a small number, approximately 70 of the eldest, speak the language fluently. Franz Boas conducted extensive research on the language in the early 1900s.

| Coast Tsimshian | Translation |

| Way dankoo | Thank you |

Challenges in Spoken Languages of Alaska

The following are the challenges of languages spoken in Alaska.

| Challenge | Description |

| Lack of Inter-generational Transmission | The transmission of these languages from older to younger generations is declining, leading to fewer native speakers. |

| Educational Challenges | Limited resources and opportunities for learning languages in formal education hinder efforts to revitalize and sustain these languages. |

| Linguistic Diversity | Managing and preserving 23 distinct languages with unique characteristics and dialects presents logistical and educational challenges. |

| Government Support | While symbolic recognition has been granted to Alaska Native languages, more substantial governmental support and policy frameworks are needed for effective preservation. |

| Integration with Modern Society | Balancing the preservation of traditional languages with the practical demands of modern society poses challenges in maintaining language relevance and usage. |

Conclusion

The spoken languages of Alaska are more than just ways to communicate. They are threads that weave together the rich tapestry of Alaska’s cultural heritage. Despite the efforts to preserve them, many languages need help with the dwindling numbers of fluent speakers. However, initiatives by the Alaska Native Language Center and local communities are vital in keeping these languages alive. Learning and understanding these languages connects you with Alaska’s past and helps preserve its unique identity for future generations. Each language, from Iñupiaq to Tlingit, carries centuries of stories, traditions, and knowledge. By supporting these preservation efforts and appreciating the beauty of Alaska’s linguistic diversity, you play a crucial role in safeguarding this invaluable aspect of Alaska’s cultural legacy.