What was once a perfectly straight stretch of the Richardson Highway now bears visible scars of one of North America’s most powerful earthquakes. On November 3, 2002, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake along the Denali Fault ripped through central Alaska, violently reshaping the landscape in seconds.

The fault rupture caused the ground to move up to eight feet (2.4 meters) horizontally, bending and displacing sections of the highway that had once run in a straight line through the rugged interior terrain. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Denali Fault event remains one of the largest strike-slip earthquakes ever recorded in the continent’s interior.

Despite the extreme force of the quake, Alaska’s critical energy infrastructure withstood the event remarkably well. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), which runs parallel to the fault in the same region, was designed with sliding support systems that allowed it to flex and absorb seismic energy. These engineering measures prevented any rupture or oil spill, a success often cited as a model for earthquake-resilient design.

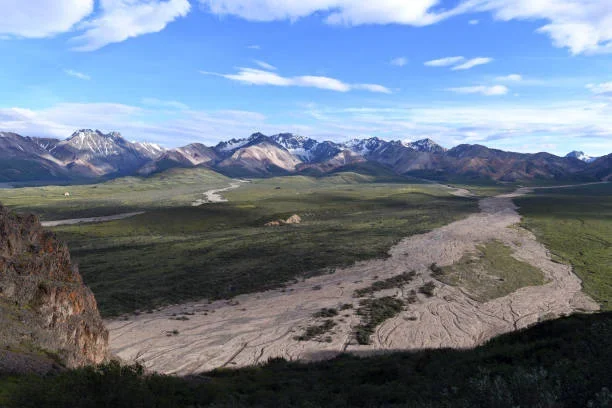

The Denali Fault extends more than 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) across Alaska and into Canada’s Yukon Territory. During the 2002 event, the fault rupture propagated for more than 340 kilometers (211 miles), shaking the state for over a minute and causing landslides, rockfalls, and ground cracks visible from the air.

Communities in Fairbanks, Delta Junction, and Tok experienced intense shaking, though Alaska’s remote geography limited damage to populated areas. Researchers later determined that the earthquake released energy equivalent to 1,000 atomic bombs, making it one of the most powerful continental earthquakes of the modern era.

Today, the scarred alignment of the Richardson Highway stands as a visible reminder of Alaska’s geologic volatility. The site has become an educational point of interest for geologists, engineers, and travelers exploring the Denali region.